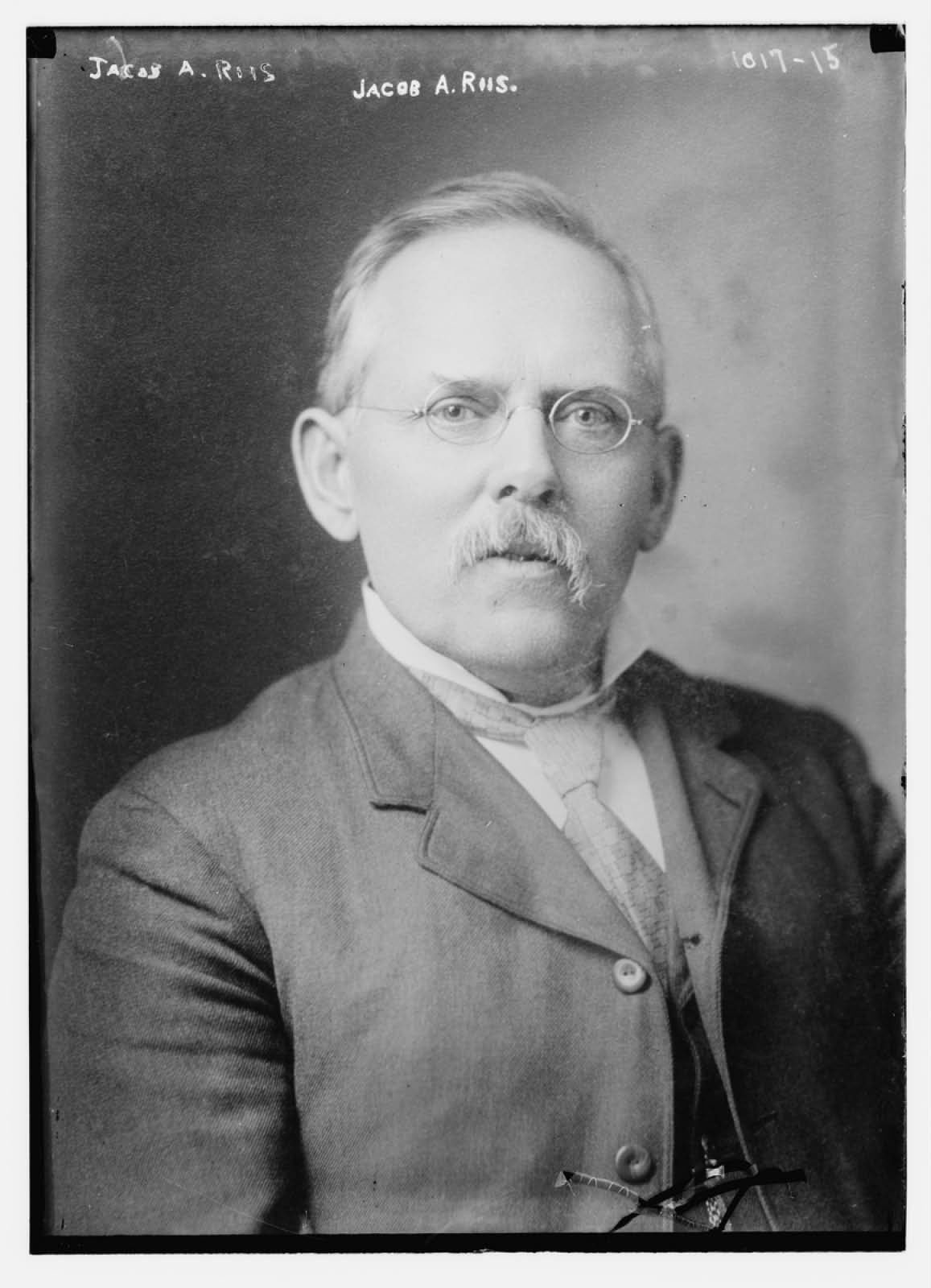

Jacob A. Riis fought for his cause in many arenas and used many different media. He was a journalist, photographer, author, and lecturer and ended up as an important social reformer.

After working several menial jobs and living hand-to-mouth for three hard years, often sleeping in the streets or an overnight police cell, Jacob A. Riis eventually landed a reporting job in a neighborhood paper in 1873. He found his calling as a police reporter for the New York Tribune and Evening Sun, a role he mastered over a 23 year career. In this role he developed a deep, intimate knowledge of the workings of New York’s worst tenements, where block after block of apartments housed the millions of working-poor immigrants. Cramming in a room just 10 or 11 feet each way might be a whole family or a dozen men and women, paying ‘5 cents a spot’ – a spot on the floor to sleep.

Riis’ hallmark was exposing crime, death, child labor, homelessness, horrid living and working conditions and injustice in the slums of New York. He blended this with his strong Protestant beliefs on moral character and work ethic, leading to his own views on what must be done to fight poverty when the wealthy upper class and politicians were indifferent. Later, Riis developed a close working relationship and friendship with Theodore Roosevelt, then head of Police Commissioners, and together they went into the slums on late night investigations. Many of the ideas Riis had about necessary reforms to improve living conditions were adopted and enacted by the impressed future President.

Today, Riis’ photos may be the most famous of his work, with a permanent display at the Museum of the City of New York and a new exhibition co-presented with the Library of Congress (April 14 – September 5, 2016). However, Riis himself never claimed a passion in the art and even went as far as to say “I am no good at all as a photographer”. Rather, he used photography as a means to an end; to tell a story and, ultimately, spur people into action. This was verified by the fact that when he eventually moved to a farm in Massachusetts, many of his original photographic negatives and slides – over 700 in total – were left in a box in the attic in his old house in Richmond Hill. His materials are today collected in five repositories: the Museum of the City of New York, the New York Historical Society, the New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, and the Museum of Southwest Jutland.

After a series of investigative articles in contemporary magazines about New York’s slums, which were accompanied by photographs, Riis published his groundbreaking work How the Other Half Lives in 1890. It became a best seller, garnering wide awareness and acclaim. He went on to write more than a dozen books, including Children of the Poor, which focused on the particular hard-hitting issue of child homelessness.

Riis recounted his own remarkable life story in The Making of An American (1901), his second national best-seller. It told his tale as a poor and homeless immigrant from Denmark; the love story with his wife; the hard-working reporter making a name for himself and making a difference; to becoming well-known, respected and a close friend of the President of the United States. Today, this is still a timeless story of becoming an American.

The success of his first book and new found social status launched him into a career of social reform. He had mastered the new art of a multimedia presentation using a ‘magic lantern’, a device that illuminated glass photographic slides on to a screen. Riis became sought after and travelled extensively, giving eye-opening presentations right across the United States. He was determined to educate middle-class Americans about the daily horrors that poor city residents endured. Arguing that it is the environment that makes the person and anyone can become a good citizen given the chance, Riis wished to force reforms on New York’s police-operated poorhouses, building codes, child labor and city services.

More than just writing about it, Jacob A. Riis actively sought to make changes happen locally, advocating for efforts to build new parks, playgrounds and settlement houses for poor residents. Many of these were successful. For example, after ‘ten years of angry protests and sanitary reform effort’ came the demolishing of the Mulberry Bend tenement and the creation of a green park in 1895, known today as Columbus Park.